These orders and memoranda touch on nearly all areas of immigration enforcement, including the treatment of immigrant children.

March 2017 ILRC guidance addresses possible ways that UACs may be affected by these changes.

We do not know how these policies will play out in practice, and there will likely be legal and advocacy challenges to their implementation.

Limiting Who Can Be Considered a UAC.

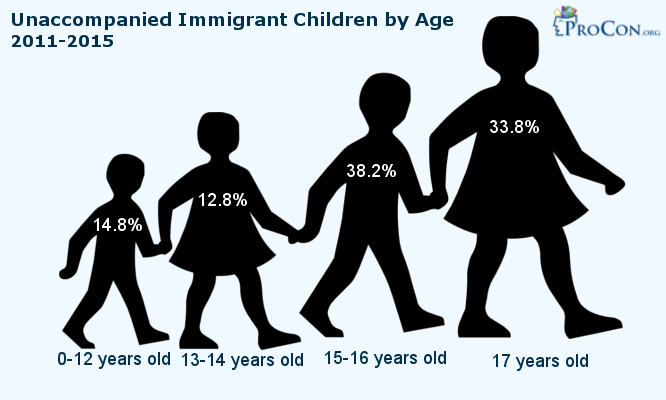

UAC is defined as a child who:

1) has no immigration status in the U.S.;

2) is under 18 years old; and

3) has no parent or legal guardian in the U.S., or no parent or legal guardian in the U.S. who is available to provide care and physical custody.

When children from non-contiguous countries are apprehended by Customs & Border Protection (CBP) or Immigration & Customs Enforcement (ICE), those agencies must notify the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) within 48 hours, and transfer the child to HHS within 72 hours of determining them to be a UAC.

Such notice and transfer are also required for UACs from contiguous countries, provided that they trigger trafficking or asylum concerns or are unable to make an independent decision to withdraw their application for admission.

Many UACs are apprehended by CBP at the border, such that even those who do have parent(s) in the U.S. typically do not have parents that are “available to provide care and physical custody” in the short time in which CBP must determine if the child meets the UAC definition. Because of this, some children are classified as UACs even though they have a parent in the U.S., consistent with the definition’s disjunctive third prong.

Under previous USCIS guidance and practice, once a child is classified as a UAC, the child continues to be treated as a UAC, regardless of whether they continue to meet the definition. The UAC designation is generally beneficial because the law provides for more child-friendly standards for UACs. In an apparent effort to limit the number of youth who are classified as UACs, the Dept. of Homeland Security (DHS) Memorandum implementing the recent Executive Order on border enforcement (“Border Enforcement Memo”) directs U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Services (USCIS), CBP, and ICE to develop “uniform written guidance and training” on who should be classified as a UAC, and when and how that classification should be reassessed.5 This guidance has not yet been developed.

But we anticipate that we may see any or all of the following changes:

-- Fewer children being classified as UACs upon apprehension. This could result in these children being subject to expedited removal (fast-track deportation without seeing an Immigration Judge), rather than being placed in removal proceedings under INA § 240, as the law requires for all UACs from non-contiguous countries and those who pass the screening from contiguous countries.

-- This could also result in more children being detained by DHS in detention centers rather than by HHS in less restrictive settings.

-- Children who are initially classified as UACs being stripped of that designation—formally or informally--once they turn 18 and/or reunify with a parent and/or obtain a legal guardian.

Federal law offers certain benefits to UACs. Losing that designation may deprive the affected children of those protections, meaning that they may:

1) no longer be able to avail themselves of the provision of law that allows UACs to file their asylum applications with USCIS in a non-adversarial setting despite being in removal proceedings;

2) be subject to expedited removal after being released from HHS custody rather than being placed in removal proceedings under INA § 240;

3) not receive post release services from HHS;

4) no longer be eligible for certain government-funded legal representation programs for UACs; and

5) no longer be eligible for voluntary departure at no cost.

Punishing Sponsors & Family Members of UACs

The Border Enforcement Memo also seeks to penalize parents, family members, and any other individual who “directly or indirectly . . . facilitates the smuggling or trafficking of an alien child into the U.S.” This could include persons who help to arrange the child’s travel to the U.S., help pay for a guide for the child from their home country to the U.S., or otherwise encourage the child to enter the U.S.10 Pursuant to the Border Enforcement Memo, enforcement against parents, family members or other individuals involved in the child’s unlawful entry into the U.S. could include (but is not limited to) placing such person in removal proceedings if they are removable, or referring them for criminal prosecution. We do not know how this provision will play out in practice.

But even the inclusion of this language in the memo may cause panic and dissuade parents, family members or other adults from 1) sending children to the U.S. (typically done when children face imminent harm in their home country); 2) sponsoring children out of HHS custody once they are in the U.S.; 3) assisting in children’s applications for immigration relief, including asylum; 4) otherwise assisting children in fighting against deportation.

Criminalizing Young People

Under the DHS memo implementing the Executive Order on interior enforcement, DHS’s enforcement priorities have been vastly expanded. While DHS previously focused its resources on removing people with serious criminal convictions, now DHS will take action to deport anyone it considers a “criminal alien.” The current administration’s definition of a criminal alien is incredibly broad, including people with criminal convictions, but also those charged with criminal offenses, or who have committed acts that could constitute a criminal offense.

Immigration law has long treated juvenile delinquency differently than criminal convictions, and that law is unchanged. However, it is unclear given the broad scope of the new enforcement plan whether delinquency will be considered a “criminal offense” and thus a priority for purposes of enforcement (even though it may not make a person inadmissible or deportable under the immigration laws). It remains to be seen how these expanded enforcement priorities will play out.

See a new March 2017 guidance here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed