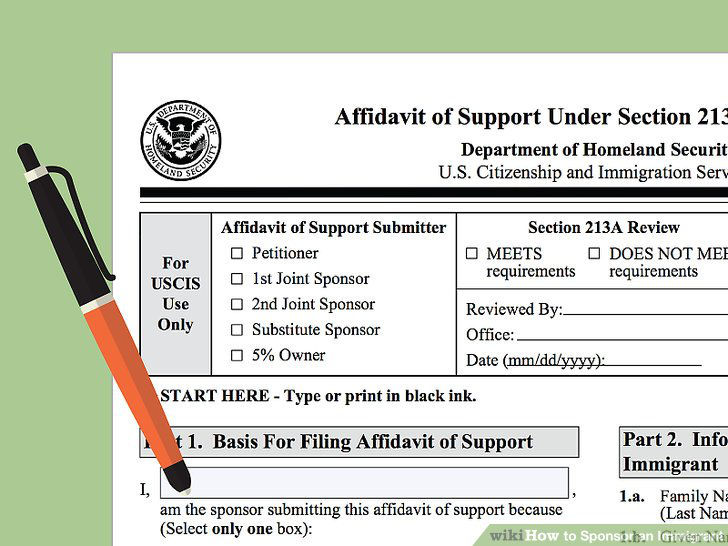

If you are applying for adjustment of status (USCIS Form I-485), or an immigrant visa (Form DS-260), and need the Affidavit of Support, USCIS Form I-864, effective 03/01/2025, you must use the HHS Poverty Guidelines for 2025 to complete Form I-864, Affidavit of Support Under Section 213A of the INA.

These poverty guidelines are effective beginning Mar. 1, 2025.

Начиная с 1 марта 2025 вступили в силу новые рассчеты уровня бедности для подачи Аффидевита о Материальной поддержке для получения вида на жительство или грин карты в США.

Таблица с 100% и 125% рассчетами опубликована тут. Таблица на 2025 год разделяет категории по количеству членов семьи и по штатам (все штаты, и отдельно Гавайи и отдельно Аляска).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed